That question, in one form or another, has been challenging policy makers for decades. Grand national strategies, like the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, Head Start, and the No Child Left Behind Act, have been promoted by presidents and passed by Congress to help address the problem through expensive programmatic and instructional interventions. But what if the solution to the achievement gap is to be found in other domains, such as school culture, family support, or religious commitment?

On April 3 at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C., Dr. William H. Jeynes, a professor at California State University at Long Beach and a scholar with the Baylor Institute for Studies of Religion, released a study showing that the achievement gap between majority students and minority students, as well as between students of high- and low-socioeconomic status, is significantly narrower in religious schools than in public schools. The study also found that “when African American and Latino children who are religious and come from intact families are compared with white students, the achievement gap disappears.”

Jeynes drew much of his data from the massive National Education Longitudinal Survey (NELS:88), which tracked a nationally representative sample of eighth graders through high school and beyond. NELS:88 provides data on a host of school and student variables, allowing Jeynes to look at whether schools were religiously affiliated and to examine other factors like school culture, curriculum, race relations, discipline, violence, and homework practices. The student questionnaire enabled Jeynes to isolate students who considered themselves “very religious,” those who were actively involved in religious youth groups, and those that regularly attended religious services. He also examined other variables, such as test results, socioeconomic status, race, gender, and family structure.

The NELS data showed that twelfth-grade religious school students in all SES quartiles achieved at higher levels than their counterparts in public schools, with the religious school advantage being highest for students in the lowest SES quartile. Religious school students in the bottom SES quartile had a 7.6 percent advantage in reading scores over similar public school students, while students in the highest SES quartile had a somewhat lower 5.2 percent advantage.

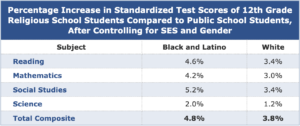

Looking at achievement by race, Jeynes found similar results: higher overall achievement for both minority and majority students in religious schools when compared to their counterparts in public schools, but with minority students (i.e., African American and Latino students) enjoying an even greater religious school advantage than white students. For example, before controlling for gender and SES, black and Latino students scored 8.2 percent higher than their public school counterparts in reading achievement, while white students scored 6.0 percent higher than their counterparts. But even after controlling for gender and SES (see chart), black and Latino students outscored their public school peers in reading by 4.6 percent, while white students did so by 3.4 percent.

With the achievement advantage among religious school students greater for low-SES students than high-SES students and greater for minority students than majority students, Jeynes concluded that both the SES and racial achievement gaps are narrower in religious schools than public schools.

Turning to the more complicated question of why religious schools have a narrower achievement gap, Jeynes examined factors relating to school culture, family, social capital, and religious commitment. Although the methodology did not allow a determination of the cause or causes of the higher student performance in religious schools, the study offered some interesting candidates and correlations.

Exploring the role played by school culture, Jeynes statistically examined five separate components, namely, school atmosphere, racial harmony, level of school discipline, school violence, and amount of homework done. According to the report, “The results demonstrate that religious schools outperform nonreligious schools in all of the five school trait categories and in nearly all of the individual questions that make up those categories.” The study also found that religious school students enjoyed an advantage over public school students in the three learning habits that were most strongly related to academic achievement: taking harder courses, diligence, and overall work habits.

Jeynes reviewed the research literature for clues about other possible explanations for private school achievement. Parental involvement, religiously committed parents, intact families, and caring teachers were all potential contributing factors. Jeynes also explained that religious schools encourage a religious commitment among students, which could affect achievement because of an associated religious work ethic, a stronger internal “locus of control,” and “the tendency for religious people to avoid behaviors that are typically regarded as undisciplined and harmful to educational achievement.”

In connection with what he described as one of the study’s most notable findings, Jeynes looked at what happens to the achievement gap for religiously committed students from intact families. He found what he called an “amazing” result: “The achievement gap disappears.” Put another way, “[W]hen the data are adjusted for SES and gender, black and Hispanic adolescents who are religious and from intact families do just as well academically as white students.”

Turning to the policy implications of the study, Jeynes suggested that “showing that factors as simple as religious commitment, religious schools, and family structure can reduce or eliminate the gap may inspire educators and social scientists to encourage policies that are supportive of faith and the family so that the gap can be narrowed significantly.” He argued that including private schools in school choice initiatives “conceivably could improve the overall quality of the U.S. education system,” and he suggested that public schools “can benefit by imitating some of the strengths of the religious school model.”

Jeynes concluded that “religious education is a vibrant part of the education system in the United States” and called for further study on “why students from religious schools outperform students in public schools.”